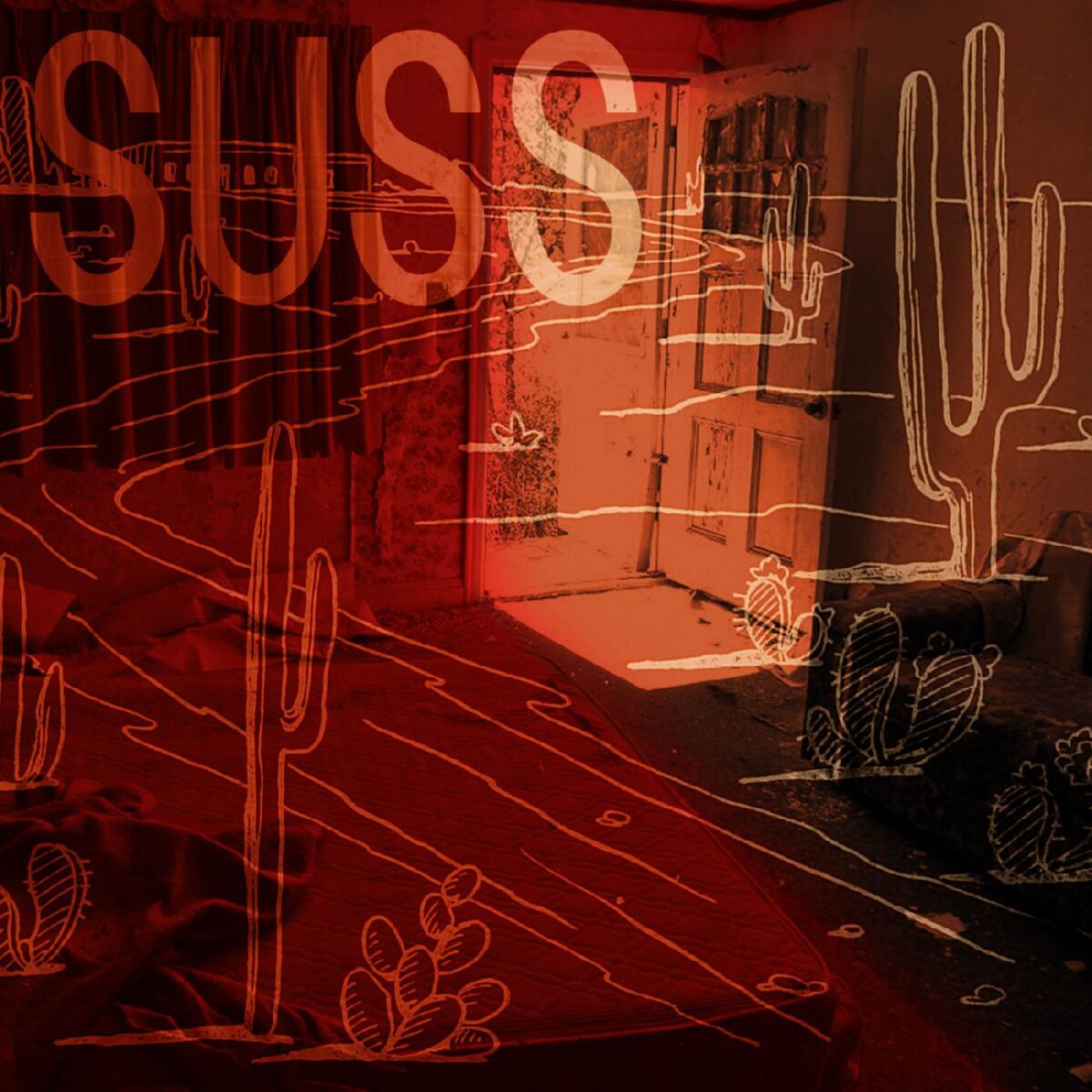

SUSS - Ghost Box

SUSS - Ghost Box

Northern Spy Records

Couldn't load pickup availability

Record Label: Northern Spy Records

Catalog Number:

Release Date:

Genre: Ambient and Americana

What would it sound like if ambient pioneer Brian Eno had produced the Western film scores of Ennio Morricone? We’ll never know, but we’re now a step closer thanks to Ghost Box, the debut album by SUSS, an NYC quintet whose members have worked in various capacities with Lydia Lunch, the B-52s, Rubber Rodeo, k.d. Lang, David Bowie, John Cale, Ed Sheeran, Wilco, Norah Jones, The War On Drugs, Burt Bacharach, and countless others. More than a literal reconstruction of an imagined collaboration between Eno and Morricone, Ghost Box opens a door onto a world where ambient music and country-western make for natural bedfellows.

That world, as it turns out, is the one we already live in -- it just took someone to make the connection. For Grammy-nominated multi-instrumentalist and cowpunk pioneer Bob Holmes, that connection has been hiding in plain sight for decades. The catalyst behind SUSS, Holmes views electronic acts like Boards of Canada and shoegaze icons like My Bloody Valentine as more recent avatars of the “high lonesome” vibe that we tend to think of strictly in terms of traditional roots music. In that light, you can trace the melancholic sprawl of classic titles by both of those acts back to Hank Williams. Looking at that lineage in reverse then begs the question: What is twang, anyway, if not a form of ambiance?

Ghost Box, then, embodies “ambient country music” not as a gag or a novelty or even a postmodern recontextualization, but instead as the organic offspring of forms that, in a sense, were already conjoined. One of the album’s charms, though, is that the rest of SUSS didn’t necessarily see it that way. So it required quite a bit of exploration as a group -- Holmes on mandolin and guitar, guitarist/keyboardist Pat Irwin, pedal steel player Jonathan Gregg, synth looper/visual artist (and New Yorker/New York Times illustrator) Gary Leib, and William Garrett, architect of the “high lonesome” quality in the album’s mixing stage -- to arrive at a blend that felt natural.

"In the past,” says Holmes, “Gary and I were well known as the guys who mashed-up Dolly Parton and Devo -- but you could see the stitches. This time, we wanted to make music where you couldn't see the stitches.”

The goal, in a nutshell, was to create ambient music using (mostly) traditional instruments -- a kind of reverse-engineering of Holmes’ longstanding conviction that electronic music is today’s folk expression. Ostensibly, Ghost Box achieves what Holmes was aiming for, but it also accomplishes much more. As tumbleweeds continue to blow across the screen of modern musical fashion, artists appear to yearn for the mythical America of yore as if they could somehow get there by re-creating vintage sounds.

Today, we’re practically inundated with music that evokes the hills of Appalachia, the never-ending Western sky, the hallowed halls of the Grand Ole Opry, and so on. Sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference between reverence for these cultural artifacts and a fascination with them as kitsch. In both cases, the resulting music can exude the fragrance of social archeology. Ghost Box echoes from a more genuinely inviting musical landscape where the cowboy-hatted Brooklynite and the native Kentuckian are no longer confined to their respective stereotypes as tourist and tourist attraction.

Whatever your frame of reference, wherever you stand when it comes to notions of “authenticity,” Ghost Box will transport you, as Irwin puts it, to “other places.” Irwin, who shares Holmes’ love of Brian Eno but “wasn’t totally familiar with” the ambient country direction Holmes wanted to pursue, sums up one of the album’s most enticing qualities when he admits that “we don’t even know where those places are.”

The course this band is charting, he notes, “is something we’re discovering as we go along.”

Share